In the first class of one of the first courses I took in college, I learned a mind-shifting lesson. Majors, or "concentrations" as we called them at Brown, are not just sets of knowledge and skills to learn, though those are important. Every major also holds a hidden gift: a lens. A lens with which to see the world in a distinct way. A lens with which to focus the shining sun of our mind on the world's problems.

For example, a few years ago, I thought about the lenses which

mathematics and computer science offer. Each of us actually has several lenses, but we usually only spend time with one or two. Many of us spend decades polishing one lens during our career. We might spend years in graduate school trying to get a clear view of some subject, hoping we have the right lens to do so.

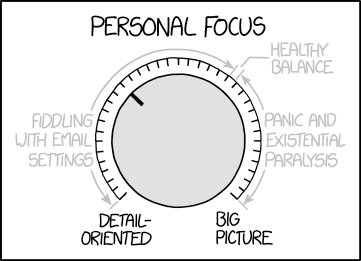

Sometimes Often we argue about problems or facts, because we use different lenses and can't trade. We may also get stuck using our lens at a certain distance, or tunnel in so much that we can't see anything at all. I certainly had the latter experience while on trauma call, as I fixated on the face of a dying man I was helpless to save. In such situations, how do we change focus? How can we zoom out to see the big picture rather than auto-focusing on the nearest, shiniest stimulus? How can we focus mindfully on one subject to avoid getting distracted? How can we switch lenses to see a problem in a whole new way?

Part of my medical school training is working out my own answers to these questions, but we have had help. We discover a special lens or two to look

inside our own minds at other lenses, to see if they're cracked, or if we're not using them correctly. In our last Learning Communities session, my college discussed ways to tell that it's time to step back. For each step in this metacognitive skill, I think there is room to improve with effort:

- Recognizing that it's time to switch: Practice with metacognition; notice tunnel vision or willful ignorance; note when things are not going as I expect.

- Zooming out: In my photography, it's become habit to zoom out and refocus when I lose sight of my subject. Likewise, I expect that practicing stepping back when non-urgent but unexpected issues arise will help me do the same in the midst of a critical event.

- Building a collection: To pick a new lens, I need a collection to choose from (hopefully in polished condition). The best lesson I've learned here is to look for new lenses everywhere - in books, in people, in classes. To keep them in good repair, it's best to try out a variety as often as I can; this is the more effortful task.

- Picking a new lens: This is the hardest part right now. I would like the ability to do this in an automatic System 1 blink as well as the option of running through my top choices systematically. Every lens has certain features they work well on; it'll take some work to identify them.

We all have our favorite tools, hammers, lenses, etc. And that's fine. We can't learn and do everything ourselves, and the diversity makes collaboration productive and conversation interesting. Manually focusing deliberately is hard work and hard to learn, and our lightning-fast auto-focus usually gets it right anyway. Yet when reality doesn't match our mental models, when we get tunnel vision, when we fail to understand each other...we should be able to adapt when the world requires it of us.

No comments:

Post a Comment